My new book is out!

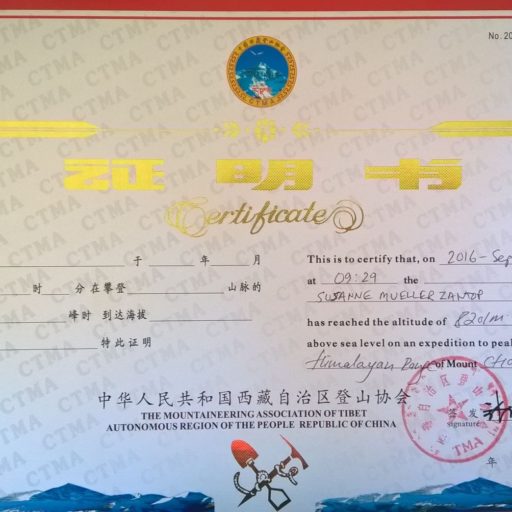

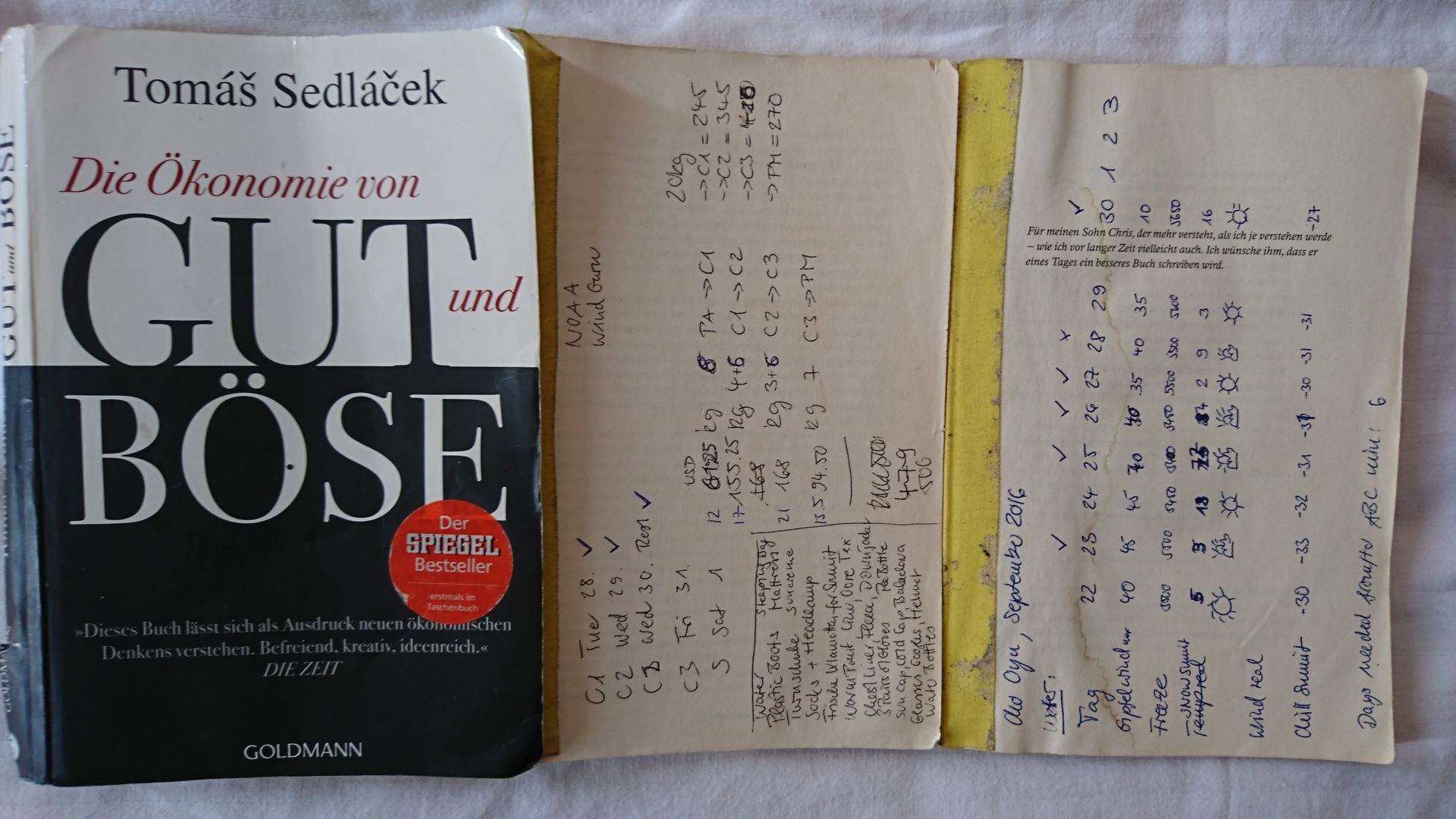

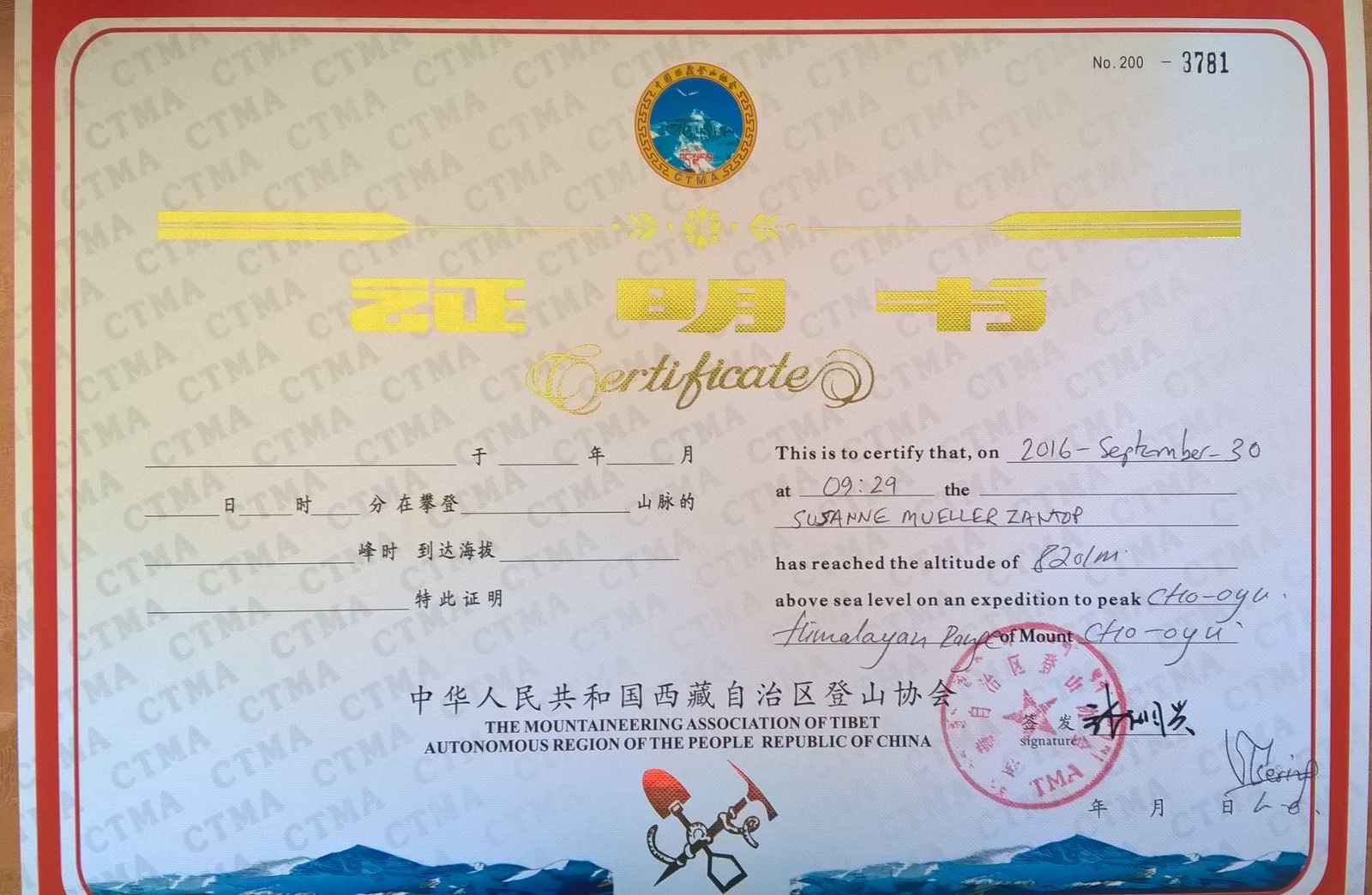

Follow me on a small trail to Gasherbrum II in Pakistan, right up to to a fateful decision that will change the course of events and redefines how success is achieved. This is for anyone seeking guidance on their expedition on the Baltoro Glacier towards K2, in the boardroom, or anywhere in between.